AND ITS SOUNDTRACK

BY

aka Epoch Collapse

In its day, 2001: A Space Odyssey was one of the most talked-about films. The film divided audiences over all aspects of mise-en-scène and narrative: dialogue, sets, use of technology, music – and silence - not to mention the ‘enigmatic’ ending.

Especially in terms of a purely audio-visual experience, 2001 is still an important and highly influential film [to put it mildly!]. Now, 33 years later in the film’s projected year one can still refer to it as a masterpiece, part of its uniqueness owing somewhat to its novel use of classical music.

With this analysis, my strategies were to give an overview - a broad spectrum of opinion and insights - on Kubrick’s intentions; the history and philosophy of film and film music; and also the responses of critics and the public (or the responses implied by the related information). Because of the predominantly audio-visual nature and minimal dialogue, the narrative structure and plot had to be detailed more than would normally be necessary.

2001 is a meditation on the question of extraterrestrial intervention and its influence on the process of human evolution, it is, in Kubrick’s words: a “mythological documentary” (Walker, 1973: 241). It covers 4 million years, from the opening scene ‘The Dawn of Man’ in the Pleistocene era to the space technology of the 21st century. It is also a meditation on the paradox of civilization and dehumanisation; lots of questions are raised regarding metaphysics, theology, cosmology, the impact of technology on man’s consciousness, and his role in the universe of space and time.

“One was asked to experience it like a piece of sculpture, before one tried to understand it” (Walker, 1973: 242). The film being so predominantly visual, the role of the music becomes essentially intrinsic to its overall form.

The narrative structure is not like any other film of the time – it may be argued that it compares more with silent films on some levels, both aesthetically and audio/visually - in fact, 2001 dared to break from the post-silent cinematic tradition of telling a story largely through words. What Kubrick did that was radical was to bridge the gap between experimental non-narrative film and the traditional plot-driven film - or more, to assimilate and transcend the limitations of both extremes. So, even though the abstract and 'psychedelic' sequences in 2001 owe much to the experimenta of the silent era and more especially to the films of such mystic film luminaries as Jordan Belson and the Whitney brothers of the early sixties; 2001 achieved so much by utilizing such experimentation and developing the 'metaphorical narrative' within a large canvas.

[C] The opening credits are accompanied by Richard Strauss’s Thus Spake Zarathustra: It is elaborate and spectacular, yet, as with all Kubrick’s films, he doesn’t believe in wasting money on overly long and protracted credits – the music and the accompanying images are sufficient to instil drama and a feeling of anticipation.

[1a] The film begins with a long silence where only the noises of two clans of hominids, some tapirs and a leopard are heard. [1b] The first appearance of the monolith introduces the dies irae of György Ligeti’s Requiem, a very challenging and hypnotic piece replete with microtonal clusters, soaring overwhelmingly powerful wordless voices and orchestral sonorities conjuring supernatural states of mind – a sonic wormhole into the infinite. The music is almost too profound for the clumsy and trepid kinaesthetic response of the hominids to the irresistible black surfaces of the monolith. But of course the music is an expression of the inexpressible – the alien intelligence that dwarfs prehistoric man.

“Historically, dissonance – harsh, controversial, disconcerting sounds – has been treated in films as negative factor implying neurosis, evil” [etc.] (Bazelon, 1975: 88). However, in Space Odyssey this music – Ligeti’s – is used to evoke feelings of awe, almost reverence for the unknown, the terror experienced is part of the fabric of wonderment not abhorrence. In this I am certain the music succeeds admirably; this is more a compliment to the composer than to Kubrick, yet it took the director’s visionary powers to fuse it with the image.

Ligeti’s Requiem dissolves, leaving a residue of the ‘new man’ consciousness in the apes [1c]. [1d] The C-G-C chords of Strauss’s Zarathustra thump triumphantly as the camera tilts upward from the foot of the monolith to the famous shot of Earth, Moon and Sun in orbital conjunction – seen throughout the film. “The chords of Thus Spake Zarathustra reverberate more profoundly at the ‘Dawn of Man’ than any verbal commentary couched in a pseudo-Genesis style” (Walker, 1973: 245).

[1e] The sequence of the bone hurled by the most advanced ape cuts to…[2a-b-c-d]...the atomic bomb satellite and the courtly grace of Johann Strauss’s Blue Danube Waltz plunges us into what looks like a Newtonian universe of clockwork and precision. The Blue Danube and the spinning Hilton Space Station have a symbiotic relationship – the waltz gains a greater aesthetic drama when thrown into the equation of technology in the darker reaches of space. The waltz also acts as “muzak – ‘happy-music’ for space travellers” (Manvell and Huntley, 1975: 253) for the Pan Am space shuttle’s flight, delivering the space scientist to the station, the Blue Danube thereby serves many functions.

This urbane irony, in 3/4 time, the 19th century waltz of clockwork elegance aligned to the space hardware moving with 21st century precision could be seen as a cosmic Freudian docking procedure. When the orchestra swells there is a momentary lilt in the music – the breath and heartbeat of history echoing through the backdrop of mute darkness. As to why the director chose this music, one enthusiastic viewer wrote to Kubrick advancing the theory that “centuries ago 3/4 time was referred to as ‘perfect time’ and that it best described the motion of the universe” (Agel, 1970: 191). Whether this notion is spurious or not, it remains that with these juxtapositions of music and image, Kubrick has created an innovative narrative approach. The music’s most eloquent irony is in the fake Nietzschean world of man as superman and the banal dialogue abounding around his space toys while the elegant cosmic law-abiding metrical rhythm steers us through to the moon base. Via the chocolate box waltz, Kubrick’s black humour and cynicism could be asking us to question this imperfect evolution generated by simian violence to the passive-aggressive Americans of corporate interplanetary conquests.

The music is not used to emphasize a character’s action, emotion or dialogue – in fact, virtually none of the music is underscored – the music is practically on equal footing to the imagery, and together they act as a dialogue. “2001 aspired not to the condition of a science fiction novel but to that of music.” (Kubrick in Baxter, 1997: 215). About the film and the use of music and image Kubrick says: “It attempts to communicate more to the subconscious and to the feelings than to the intellect.” (Agel, 1970: 7). Of the 141 minutes of running time (originally 160) there are only 40 minutes of dialogue.

[3a] In the region of the Tycho crater on the Earth’s moon the monolith has reappeared – after 4 million years. A lunar shuttle is sent with space scientists, who, in their masked mortal nervousness discuss sandwiches and fillings. Ligeti’s Lux Aeterna is heard when we view the vehicle from the wastes of the lunar landscape, the music fades out momentarily during the empty dialogue and then fades back in as we contemplate with the astronauts what lies ahead at Tycho. I feel this is a mistake; dialogue at this point serves no purpose and only diminishes the quality and energy of this scene. [*EDIT - on further analysis, there is no mistake whatsoever: The dialogue, no matter how commonplace or trivial, is the whole point. This is actually Kubrick's way of delivering metadata on the flawed nature of man, and that evolution works in seemingly unreliable ways]. However, this is only a brief lapse and the return of the music restores our feelings of unearthliness. The Lux Aeterna music (scored for voices alone) has transparent yet ominous strands of sound, the voices cluster with electronic-like timbres and sometimes give the impression of souls lost in time…the spectres of an earlier odyssey…or, the premonitory voices of the future leaking into space and out of time?

[3b] The astronauts arrive at the excavation site of TMA-1, the NASA term for the monolith. For the second time we hear the awe-inspiring music from Ligeti’s Requiem – the sentinel: alien intelligence manifesting as music. The astronauts respond just as the apes did 4 million years before - tentatively touching the monolithic surface. Like typical tourists they line up - with Earthling vulgarity - for a photograph of national pride. But suddenly their myopic self-aggrandising behaviour is shattered “as if they were being mown down by machine gun bullets” (Walker, 1973: 251): it is an ear-piercing signal emanating from the monolith.

Once again the Earth and Sun are in conjunctive orbit. During this whole scene all we hear is the music and this shattering din, no dialogue has transpired (thankfully). Here again, the mystery, the realisations and questions have full impact purely through music and image; of course this is not unusual in cinema (in brief or bridging sections), but 2001 makes profound and extensive use of this.

No sooner has the deafening signal faded into our mental recesses, when the scene cuts to us finding ourselves floating in eternity – drifting with the tide of the Discovery on the Jupiter Mission 18 months later. [4a] The Adagio from the Gayaneh ballet suite of Aram Khachaturian is the only music that features in this section of the film; this and the extended silences help to imbue a feeling of isolation. While the only two conscious astronauts engage in on-board procedures in unemotional numbness, the Armenian melodic lines of the Adagio unfold forlornly. However, despite the sombreness of this music, there is a floating, mysterious quality here that seems to etch into the fabric of space. The slowness of the Adagio seems to correspond perfectly with the motion of bodies in weightlessness (celestial mechanics).

[4b] A growing concern about a possible computer malfunction develops. This sequence is without music, both astronauts don’t realise their discussion regarding HAL is being lip-read, the suspense created by our realisation of this builds, and then…cuts climactically for intermission.

[4c] When the cybernetic conflict finally occurs between man and machine and all but one astronaut are terminated, the film doesn’t assault us with clichéd ‘conflict music’. Instead we find ourselves in the silence of space as the lone astronaut David Bowman goes through various space-walking manoeuvres. The claustrophobic sound of Bowman’s breathing is all we hear right through to the disengaging of the computer HAL’s higher cortical functions. With the rhythm of breath the tension mounts, and during this sequence we the audience are breathing those breaths, and through this identification are made more acutely aware of the vast vacuum surrounding us.

The computer’s voice has been bland but somehow more human and emotional than anyone else’s throughout the whole film – the paradox of evolution and artificial intelligence. This narrative theme hits home even more poignantly as HAL sings the only song in the film while Bowman performs the lobotomy. The sound of human breathing acts as a counterpoint to the machine’s swan song.

[5a] The third part ‘Jupiter and Beyond the Infinite’ opens with the monolith gleaming in the light of celestial bodies against the blackness. For the third time we are thrust into the astonishing realm of Ligeti’s Requiem, the following sequences are some of the most extraordinary ever filmed in the history of cinema. “Kubrick’s ambition in 2001 is, in some ways, to return to cinema the notion of film as experience, a notion that has often taken second place to the medium’s narrative aspirations.” While one of the film’s concerns is the experimenting with narrative, “it seems equally concerned with creating a visual and aural experience so unique that audiences will feel that they are experiencing film for the first time.” (Falsetto, 1994: 48)

“The nine moons of Jupiter are in orbital conjunction (a near-impossible astronomical occurrence)” (Agel, 1970: 221). This occurs as Bowman, in pursuit of the monolith, is plunged into the stargate –there is a musical montage at this point where two pieces by Ligeti overlap – the Requiem and the orchestral work Atmospheres. [5b] Atmospheres provides an eerie intensification to the “abstract expressionist art work” and solarized landscapes - where the “spatial and temporal ambiguity itself becomes the subject of the sequence.” (Falsetto, 1994: 50). Kubrick’s indebtedness to avant-garde filmmakers such as Jordan Belson and the Whitneys is most apparent here, (Curtis, 1971: 170). To propel us along, Kubrick has included along with the music - random explosions or the inter-dimensional equivalent of sonic booms.

[5c] The sense of hurtling through the infinite subsides as the Lux Aeterna music filters in…[5d]…and the curious sounds of preternatural voices - fragments of Ligeti's Aventures - take us into the next sequence: the ‘Louis XVI rooms’. These strange sounds bare some resemblance to the Dadaist experiments of the twenties and musique concrète; they seem to follow Bowman as he discovers himself in startling moments of accelerated aging. “[T]he wizened chrysalis of the bedridden Bowman is raising his arm to the monolith, which has appeared at the foot of the deathbed” (Walker, 1973: 262). Bowman’s corpse is “subsumed into the monolith” and “an aureoled embryo, a perfect Star-Child” (Walker, 1973: 263) moves earthwards through space. [5e] Thus Spake Zarathustra emerges out of this scene just as the transformation has transpired, the Star-Child’s glowing eyes look back at us just as the tympani pound across the solar system and the majestic sound sustains this image of human transcendence.

Addendum: If we consider that the aliens thought that David Bowman would feel at home in an 18th century apartment (‘Louis XVI rooms’), then we can deduce that their world is situated around 250 light-years from Earth and that the world of Barry Lyndon is the latest state of humanity they have observed prior to intercepting Dave.

[E] The End Credits are accompanied by the Blue Danube Waltz. Why Kubrick chose to bring back interplanetary Vienna is uncertain and no opinions or ideas have been gleaned from the material examined. All I can suggest is that this is another touch of dry wit mixed with a hint of hope for the future of humanity, if not - its sense of humility (and humour) in this universe ‘peopled’ with beings of relative omnipotence.

The following is a recapitulation on why the film music is effective and how it successfully portrays or enhances certain actions or images throughout:

Besides its obvious associations with the theme of transcendence and the notion of the superman, Richard Strauss’s Thus Spake Zarathustra - from a purely musical point of view – bestows its visual component with enormous power. The ‘pre-recorded’ aspect does not diminish its tenor. The composer’s intentions (73 years previous) befit the theme of the film, and so (arguably) 2001 has provided an association that does not unduly affect the original aim of the music.

None of the pieces by Ligeti obey or conform to conventional notions of meter, harmony, melody, etcetera, the music is used for its poetic drama, it expresses equally well the beginning and end of the universe – infinitely ancient and infinitely futuristic. It has been argued that an original score should have been used (Alex North’s was rejected), or at least to have had Ligeti from start to finish. (Bazelon, 1975: 111). That may be a fair assertion, but very few film composers at that time could have done the film justice – Ligeti’s musical language was ‘light years’ ahead of them. Bebe and Louis Barron of Forbidden Planet fame may have been another possibility, but that’s another story. (Vale and Juno, 1994: 194).

The Blue Danube Waltz provides a wry look at the space industry and man at this stage of evolution “functions as a kind of muzak to get you up to the space station where Howard Johnson and Conrad Hilton have taken over” (Glass in Bazelon, 1975: 279). It is a double-edged sword: the waltz conveys grandeur on so many levels, tying history together. And despite the old Viennese associations “in the hands of Von Karajan the music becomes a work of art, the film helps dispel all of [those] associations, and we’re into a new audio-visual world” (Williams in Bazelon, 1975: 200).

Regarding the use of Khachaturian’s Adagio, Irwin Bazelon admits: “Moving slowly almost wistfully, the music’s undeniable linear flow suggests to a remarkable degree the calm progress of the ship through the dark vastness of outer space.” (Bazelon, 1975: 132). Interestingly, Bazelon doesn’t generally agree to the use of ‘pre-recorded’ music in film.

The rampant use of bleeping whooshing crashing noises in the majority of science fiction films is minimised and Kubrick’s scientifically accurate application of absolute silence in space allow for greater impact in terms of the music content. The latter consideration is largely ignored in nearly all other films of this ‘genre’ – deeming the public to be scientifically ignorant or unobservant.

Above all, given the subject matter, the cuing of musical episodes and the juxtaposing of these elements with extended periods of silence has created a filmic experience of such profundity. And yet, with such philosophical weight, as an art form it doesn’t lose sight of the necessity of a narrative structure (even if that be of an experimental nature), and thereby it successfully engages the audience.

But this is not an essay extolling the use of pre-recorded music in motion pictures. This is an assertion that the present film has made use of such music in a creative and remarkably innovative way.

It has been queried as to whether the use of pre-recorded music in 2001 is “a retrograde step, a return to the silent film?” (Manvell and Huntley, 1975: 253).

It is true, music was an integral part of the film experience in the ‘silent’ era, films like “Réné Clair’s ‘Entracte’(1924) and Fernand Léger’s ‘Ballet Mécanique (1924-25), in fact, abstract or ‘avant-garde’ film has depended on musical theory for much of its effect” (Monaco, 1977: 39).

James Monaco continues:

By the 1930’s Sergie Eisenstein, for his film Alexander Nevsky, constructed an elaborate scheme to correlate the visual images with the score by Prokofiev. In this film as in a number of others, such as 2001: A Space Odyssey, music often determines images.

(Monaco, 1977: 39)

However, there is nothing retrogressive about 2001 and its musical content. Given the experimental narrative structure, ambiguous imagery, and open-ended conclusion, 2001 is a film that challenged the soporific formulae of commercial entertainment. It is evident that this essentially non-verbal film invites us to actively interpret and question our senses and perceptions.

“Jean-Jacques Lebel described art as ‘the creation of a new world, never seen before, imperceptibly gaining on reality.’” (Mast and Cohen, 1979: 755)

BIBLIOGRAPHY AND WORKS CITED

Agel, Jerome (1970), The Making of Kubrick’s 2001,

New York: New American Library.

Baxter, John (1997), Stanley Kubrick A Biography,

London: Harper Collins.

Bawden, Liz-Anne (1976), The Oxford Companion to Film,

London: Oxford University Press.

Bazelon, Irwin (1975), Knowing the Score: Notes on Film Music,

New York: Arco Publishing.

Curtis, David (1971), Experimental Cinema,

Delta Publishing Co. Ltd.

Falsetto, Mario (1994), Stanley Kubrick Narrative and Stylistic Analysis,

Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group.

Lindgren, Ernst (1963), The Art of the Film,

Northhampton: John Dickens and Co. Ltd.

LoBrutto, Vincent (1997), Stanley Kubrick,

London: Penguin Group.

Manvell, Roger and John Huntley (1975) The Technique of Film Music,

New York: Focal Press.

Mast, Gerald and Marshall Cohen (1979), Film Theory and Criticism, Second Edition

New York: Oxford University Press.

Monaco, James (1977), How to Read a Film,

New York: Oxford University Press.

Vale, V. and Andrea Juno (1994), Re/Search #15: Incredibly Strange Music Volume II,

San Francisco: Re/Search Publications.

Walker, Alexander (1973), Stanley Kubrick Directs, London: Abacus/Sphere Books Ltd.

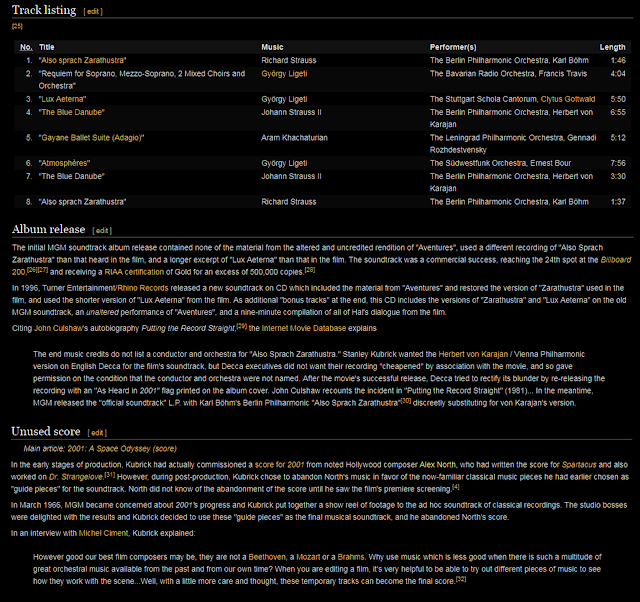

APPENDIX (Appendix 1 and 2 combined)

2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY

PLOT SEGMENTATION AND CUE EDIT

CROSS-REFERENCING, LISTING AND ANALYSIS OF MAJOR THEMES

C: Credit Titles R. Strauss: Thus Spake Zarathustra (only the music’s opening is used throughout whole film)

1: ‘The Dawn Of Man’: 4 million BCE, Australopithecines – human evolution from alien influences?

a. Silence (no music)

(Key Images: shots of landscapes from the Pleistocene era, groups of hominids and tapirs grazing on plants – hominid clans fight - leopard with dead zebra – hominid attacked by leopard)

b. G. Ligeti: Requiem – dies irae

(Key Images: Monolith’s first appearance – one clan of hominids gather around and touch it – Sun, Earth and Moon in orbital conjunction)

c. Silence (no music)

(Key Images: hominid clans fight - hominid discovers use of bone as weapon and kills rival leader)

d. R. Strauss: Thus Spake Zarathustra

(Key Images: hominid experiments with use of bone as weapon, slow-motion shots of tapirs falling to the ground)

e. Silence (no music)

(Key Images: hominid clan sit and eat the meat of slaughtered tapirs, hominid continues to play and experiment with bone as weapon – slow-motion shot: throws bone in air)

‘match cut’ from bone (primitive weapon) to atomic bomb satellite (modern weapon)

2: 2001 CE: Man’s conquest of space – the irony of human intelligence - the need for ‘national security’? – Existence of intelligent extraterrestrial life?

a. J. Strauss: Blue Danube Waltz

(Key Images: Space Station and Earth Space Craft from space, Dr Floyd and flight attendants in Earth Space Craft in zero-gravity - slow-motion shots)

b. Dialogue only (no music)

(Key Images: Dr Floyd and flight attendants in Earth Space Craft arrival at Space Station, Floyd reading zero-gravity toilet instructions, Floyd meeting with Russian scientists, Floyd’s picturephone conversation with daughter)

c. J. Strauss: Blue Danube Waltz

(Key Images: ‘Aries’ Shuttle leaving Space Station - ‘Aries’ Shuttle arrival on Lunar Base)

d. Dialogue only (no music)

(Key Images: Floyd meeting with fellow American scientists)

3: TMA-1 Excavation Site – Existence of intelligent extraterrestrial life?

a. G. Ligeti: Lux Aeterna

(Key Images: Lunar Shuttle and Lunar landscape)

b. G. Ligeti: Requiem, dies irae (signal to Jupiter at end)

(Key Images: Monolith – astronauts enter excavation by foot – astronauts touch monolith –

astronauts group around monolith for photo – signal: astronauts deafened - orbital conjunction)

4: ‘Jupiter Mission - 18 months later’ – Questions of human and artificial intelligence

a. A. Khachaturian: Gayaneh - Adagio (infrequent dialogue)

(Key Images: ‘Discovery’ craft exterior, ‘Discovery’ craft interior, Poole and Bowman involved in ‘everyday procedures’, Earth radio communications)

b. Dialogue and extended Silence (no music)

(Key Images: HAL: antenna malfunction, Bowman - in pod - space-walking – antenna, checking power unit inside, HAL lip-reading Bowman and Poole)

INTERMISSION

APPENDIX continued (Appendix 1 and 2 combined)

4: Jupiter Mission cont. – Human conflict with and eventual dominance over machine – the possibility of intelligent extraterrestrial life and its connection with Jupiter

c. Dialogue and extended Silence (no music) (astronaut breathing – HAL singing)

(Key Images: HAL lip-reading Bowman and Poole, Poole – in pod - space-walking – pod manoeuvred to attack – Poole floats off losing air, Bowman in pod to rescue Poole, astronauts in cryology: lives terminated – computer malfunction - Bowman in pod tries to re-enter ship - Bowman improvises airlock forced entry, Bowman inside HAL’s mainframe – HAL sings as lobotomization proceeds - screen image of Dr.Floyd divulging the real purpose of the mission)

5: ‘Jupiter and Beyond the Infinite’ - Is Jupiter a portal to the stars? - Is the Monolith a portal to the stars? Rebirth and Human transcendence

a. G. Ligeti: Requiem, dies irae – Atmospheres fades in at end

(Key Images: Bowman exiting ‘Discovery’, Monolith in space, Jupiter moons in orbital conjunction, Bowman in pod)

b. G. Ligeti: Atmospheres (explosions - fade out half way)

(Key Images: Bowman in pod, Bowman’s face intercut with ‘Star Gate’: alien landscapes and formations, Bowman’s eyes and colours intercut with ‘Star Gate’: alien abstractions)

c. G. Ligeti: Lux Aeterna - fade out to - (sounds of preternatural voices)

(Key Images: Bowman’s eyes - colours fading, Bowman emerging from pod)

d. G. Ligeti: Aventures (sounds of preternatural voices) – fade out to silence before deathbed

(Key Images: Louis XVI rooms, Bowman’s successively aging doubles – in space suite – at the table – in deathbed, monolith, glowing foetus merging with monolith)

e. R. Strauss: Thus Spake Zarathustra

(Key Images: ‘Star-Child’ – planets in orbital conjunction – Earth from space)

E. End Credits. J. Strauss: Blue Danube Waltz

DMR is a composer, writer, photographer, and multimedia technician who works under the moniker of Epoch Collapse. His music can be found on various sites.

Albums and tracks are available for purchase at Bandcamp (as digital downloads) :-

https://epochcollapse.bandcamp.com/

Other sites :-

https://soundcloud.com/epoch-collapse

https://epoch-collapse-music.blogspot.com/2012/12/epoch-collapse-dark-ambient-industrial.html

YouTube -

Overture - György Ligeti: Atmospheres

Tracks included are of the edited versions in the original soundtrack and not the complete works.

The Complete Soundtrack (YouTube) -

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bSOoM2ih5Is&list=PL69JX3_fW92EwY8WiTX9qlnJTrxTMRsmx&index=2&t=0s

Another album, this time from Columbia.

The album featured electronic interludes by Morton Subotnick (surname misspelt on the cover).

One drawback with this release was the fact that it didn't include Ligeti's Requiem

(the sections as used in the film).

However, the Ligeti works included are the complete originals, and not the edited soundtrack versions, which is far more satisfying a listening experience when separated from film.

Album also featured the Suite from Aniara, a space opera by Swedish composer,

Karl-Birger Blomdahl. Quite a "bonus track".

Columbia album of 2001 - TRACK LIST c/o Discogs :-

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Dawn of Man scene: On set - a coffee break, a smoke, and time to read the news.

Opening night at the Capitol Theatre (Loew's Capitol), New York City. When Space Odyssey ended its run here, the theatre was closed and soon demolished.